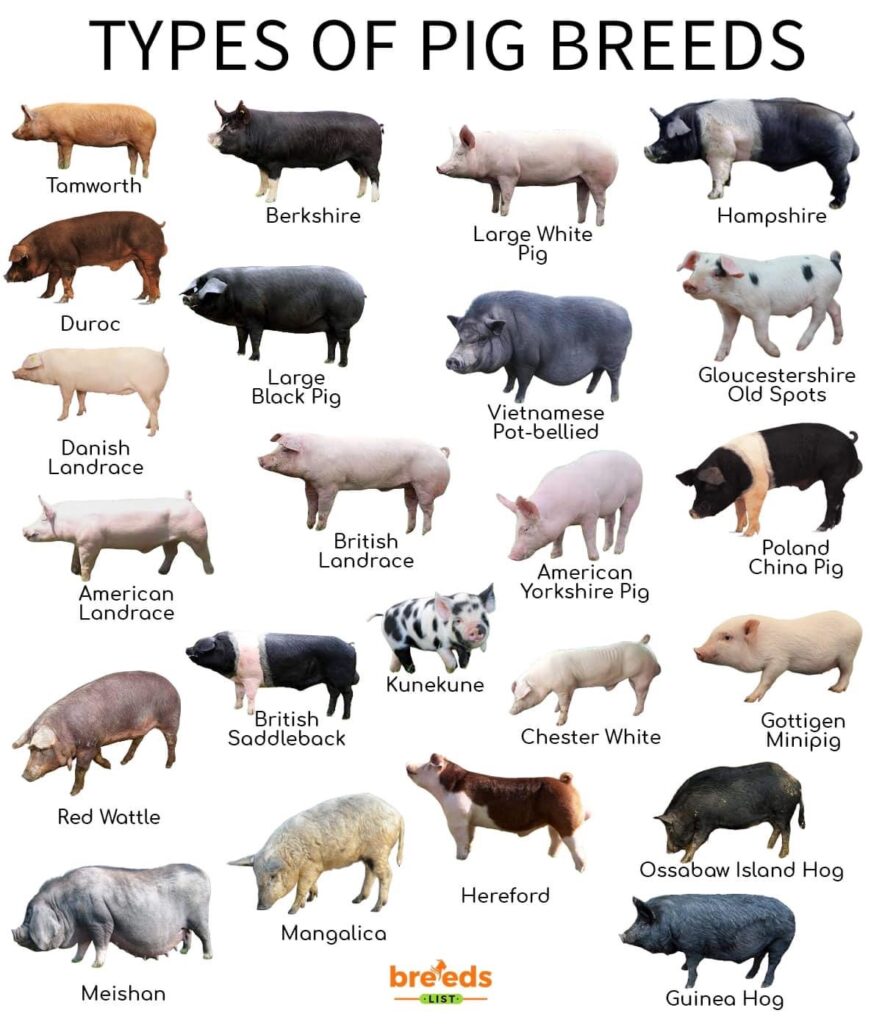

Pig Breeds, choosing the “right” one for you

I’m often asked about what breeds I think are best (for meat). My response is always the same- they are all edible. What your goals and priorities are, however, will help you decide on a breed.

I’m going to talk about pigs, because it is perfect pig buying weather! Pigs are a bit easier to raise in colder months, imo.

If what you need is something with the quickest turnaround- look no further than some of the more popular breeds such as Duroc, Berkshire, Hampshire, Chester, Landrace, Yorkshire, Poland China, and/or any cross in between. Hereford pigs are also growing in popularity. These breeds will reach maturity within 6-8mo. I would not rely on these breeds to live on pasture. I have personally used these breeds when I had lots of free scraps from restaurants, which they love. However, if you do not have this available, you’ll be looking at buying bagged feed.

If you have a bit more time, you might look into some heritage breeds such as Kunekune, American Guinea Hog, Idaho Pasture Pig, Gloucestershire Old Spot, Meishan, Mangalitsa, Red Wattle, Tamworth, and Large Black. Most of the breeds mentioned here are considered to be a ‘Lard Pig’. This means they will produce a large amount of fat, if allowed to eat a diet heavy in fatty food. But just as someone can raise a fat Yorkshire, a lean Kunekune is attainable as well, if given a breed-appropriate diet. Most of these breeds will take close to a year (or longer) to reach maturity, with Kunekune and AGH among the smallest and GOS and Large Black among the largest. These breeds are best suited on pasture, supplemented with hay in the winter.

I highly recommend doing some research on your breed and working with a reputable breeder for stock. Each breed has different needs and will have different characteristics that will help you choose what is best suited to your situation. Define what your goals are with pigs and picking a breed will become a lot clearer.

Things to consider:

-Fencing availability

-Feed availability

-Mothering instincts

-Temperament

-Purchase Price

-Size

-Foraging Ability

-Growth Rate

-Meat Preference

- Published in Ag Practices

So you got an animal to fatten up for the freezer, but when do you butcher it?

Most butchers book out months (or years) in advance! So if you don’t want to pay for any unnecessary extra feeding, you’ll need to plan this part out long before your animal is “ready” for butcher.

Generally speaking, butchering just around maturity is ideal for most animals. You utilize the full size of the animal, at it’s younger point in life for more tender meat (and less investment).

Your first place of reference is your breeder. Whomever you purchased that animal from likely has experience with that breed, specifically that blood line, can tell you approximately when they’ll reach maturity.

If you did not buy your animal from a breeder, you’ll be basing it off of breed standards and how you intend to feed it. Keep in mind, animal growth time will be higher in grain fed animals and slower in grass fed animals.

Don’t know your breed? Ask. There are so many resources here on social media and local to you that will help you determine what you have and approximately when it should reach maturity.

However, you may find yourself with an animal that isn’t in that “ideal” age range to butcher that you still need to send to freezer camp. I’m here with a little secret: they are all edible.

The reality is, when to butcher is entirely based on your needs and preference. You can butcher a suckling pig just as you can butcher a 5yr old sow at 600lbs. Are these going to yield two completely different products? Of course they are. Are they both valuable protein? Of course they are.

Whether it’s your sons first show critter perfectly timed for a butcher date, an old breeder that no longer serves you, or just an asshole escape artist that needs to go, we’re here to help time your butcher date perfectly for you!

- Published in Ag Practices

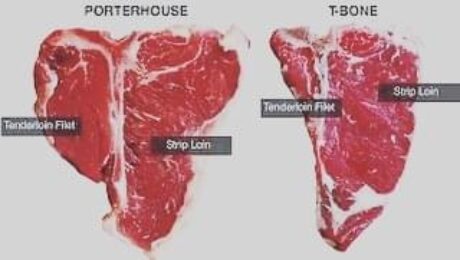

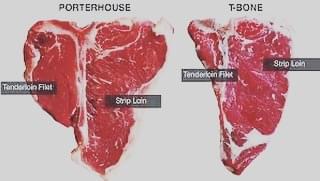

Steak Breakdown:

Pictured is the T-Bone Steak & Porterhouse Steak. Both consist of the NY Strip on one side of the bone (the spine) and the Tenderloin, also known as Filet Mignon when cut, on the other side. The difference between the two is where the cut comes from. The Tenderloin is tapered, so cuts towards the head will result in a smaller portion of the Tenderloin on the steak (T-Bone), and cuts towards the tail will include larger portions of Tenderloin on the steak (Porterhouse).

When you’re filling out a cut sheet, this is why the option is T-Bones & Porterhouses OR NY Strips & Filets.

- Published in Meat Cuts

Caul Fat

Did I butcher an animal for you? Did you receive back a little bag marked “Caul Fat”? Are you as confused as ever? Let me explain!

Caul fat goes by many different names; its technical name is the “greater omentum,” but it can also be referred to as fat netting, mesentery, lace fat, crépine (French), or ragnatela (Italian). While it doesn’t make a great fat for rendering or cooking, like kidney fat (lard) or back fat, it’s perfect for wrapping pâtés, meatloaf, meatballs, sausages, or roasts to keep them moist while they cook.

Caul Fat can withstand high temperatures. During cooking, the caul fat slowly renders out, basting the meat with fat, keeping it from drying out, and adding an extra layer of richness. Despite the fact that it surrounds the digestive organs, caul fat doesn’t have an unpleasant or “organy” flavor at all.

Tell us how you use your Caul Fat!

- Published in Meat Cuts